- Home

- About

- About SCMS

- Directors

- Artists

- Vera Beths

- Steven Dann

- Marc Destrubé

- James Dunham

- Mark Fewer

- Eric Hoeprich

- Christopher Krueger

- Myron Lutzke

- Marilyn McDonald

- Douglas McNabney

- Mitzi Meyerson

- Pedja Muzijevic

- Anca Nicolau

- Jacques Ogg

- Loretta O'Sullivan

- Lambert Orkis

- Paolo Pandolfo

- William Purvis

- Marc Schachman

- Jaap Schröder

- Andrew Schwartz

- William Sharp

- Ian Swensen

- Lucy van Dael

- Ensembles

- Concerts

- The Collection

- Recordings

- Education

- Donate

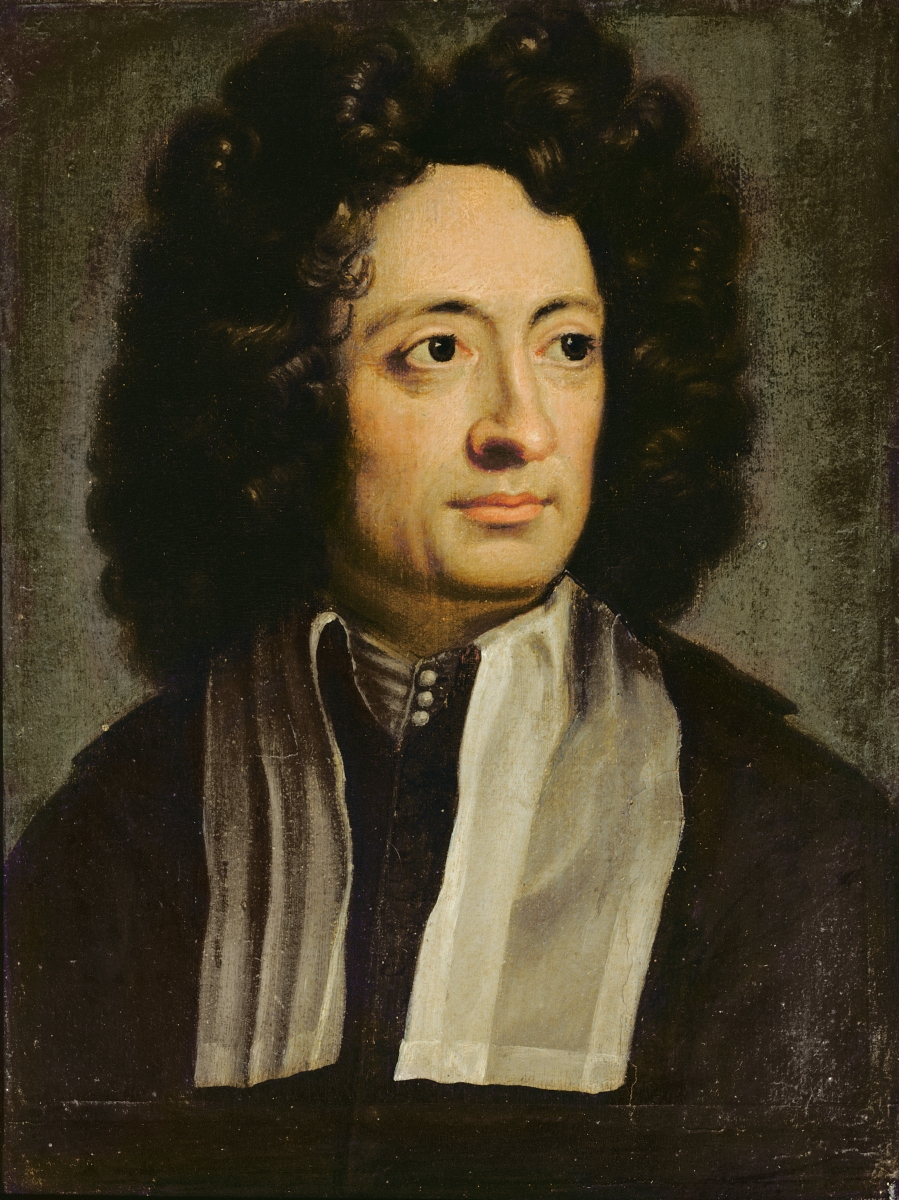

Virtuosissimo del violino, e vero Orfeo de nostri tempi

With these words (“Great virtuoso of the violin, and our contemporary Orpheus”), Francesco Gasparini, writing in his 1708 figured bass tutor, succinctly described Arcangelo Corelli, one of the most revered and influential composers of the entire baroque era. Publishing his works at the time of a remarkable boom in the music printing industry, Corelli became the first composer to derive his fame from exclusively instrumental compositions, which gained widespread recognition primarily through printed editions rather than manuscript copies. His published oeuvre, comprising four collections of trio sonatas, a set of sonatas for solo violin and continuo, and a group of concerti grossi, were among the first works to achieve “classic” stature, being played in concerts long after contemporary compositions had fallen into oblivion. Corelli’s reputation as his century’s most important violin pedagogue was upheld through the succeeding generation by his impressive roster of pupils, including, in addition to Gasparini, the Italians Pietro Castrucci, Francesco Geminiani, and Giovanni Battista Somis (and possibly Francesco Antonio Bonporti and Pietro Antonio Locatelli), as well as professional and amateur players from Spain, France, Germany, and England.

Corelli was born into a well-to-do family in Fusignano on 17 February 1653. Accounts of his early musical education are sketchy and often contradict one another, but it is clear that by 1666 he had gone to Bologna to continue his studies. Bologna, with its great cathedral of San Petronio, was an important seventeenth-century center of instrumental composition and performance, whose illustrious practitioners included Maurizio Cazzati, Giacomo Antonio Perti, Giovanni Paolo Colonna, Giovanni Battista Vitali, and Giuseppe Torelli. Corelli’s promise was quickly recognized and in 1670, at the age of seventeen, he was invited to accept a place in the Accademia Harmonica of Bologna.

Padre Martini, in his Cenni biografici manoscritti dei soci dell’Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna, states that Corelli spent only four years in Bologna. If this is true, however, Corelli’s whereabouts between the time of his admittance to the society and 1675, when he first appears in Roman payment books, listed as “Arcangelo bolognese,” remain unknown. An eighteenth-century account of a trip to France at this period, during which Corelli supposedly aroused the jealousy of Lully, is probably fictitious. Perhaps the good padre meant that Corelli spent four years in Bologna as an academy member. In any event, by May of 1679 Corelli was able to write to an official of the Tuscan court that he had accepted a position as chamber musician to Queen Christina of Sweden (resident, following her abdication, in Rome since 1655), who would receive the 1681 dedication of the twelve trio sonatas Corelli published as his Op. 1, the “first fruits of his studies.”

Corelli’s appointment to serve the Swedish queen, and his subsequent employment (1684–90) by Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili and then by Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni (1690 until Corelli’s death in 1713), offered financial security sufficient to allow him to amass by the end of his life a large and valuable collection of paintings, plus a sum equivalent to six thousand pounds sterling (as reckoned in the 1780s). This stability, in such contrast to the indigent lives of many of his musical contemporaries, afforded Corelli the luxury of restricting his composition within his self-imposed genre limits, generating a body of instrumental works from which the best could be culled for further refinement. His six published volumes thus represent an “opus perfectum,” in all likelihood only a fraction of the total number of his compositional essays. Sir John Hawkins confidently asserted in his 1776 A General History of the Science and Practice of Music that the printed pieces “were revised and corrected from time to time; and, finally, submitted to the inspection of the most skillful musicians of the author’s time.” Close acquaintance with Corellian works brings with it an appreciation of their lapidary perfection, achieved, no doubt, through just such careful polishing as Hawkins surmised.

A partial list, compiled by an eighteenth-century theorist, of several of the leading traits of the Corellian style worthy of emulation by other composers includes “the variety of beautiful and well worked-out fugal subjects, the exact observance of the laws of harmony, the firmness of the basses, and the fitness for exercising the hands of the performer.” It is a curious paradox of the kind not infrequently encountered in musical history that the very elements of this refined style that appeared revolutionary to Corelli’s contemporaries were those later imitated so often that the original models came to be perceived as somewhat flat and stale. Charles Burney, Hawkins’s great contemporary rival, noted in his A General History of Music from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period that “Corelli was not the inventor of his own favourite style, though it was greatly perfected by him,” citing Torelli and Bassani as two of his many antecedents. Though a venerable scholar of the past, Burney subscribed to the view of musical history as a continuous development reaching its zenith in his own day, and therefore lamented what he perceived as the narrow range of Corelli’s technical devices: “Though he has much more grace and elegance in his cantilena than his predecessors, and numerous slow and solemn movements; yet true pathetic and impassioned melody and modulation seem wanting in all his works.” Burney could not, however, deny Corelli’s extraordinary position in the baroque musical pantheon:

Indeed, this most excellent master had the happiness of enjoying part of his fame during mortality; for scarce a contemporary musical writer, historian, or poet neglected to celebrate his genius and talents; and his productions have contributed longer to charm the lovers of Music by the mere powers of the bow, without the assistance of the human voice, than those of any composer that has yet existed. Haydn, indeed, with more varied abilities, and a much more creative genius, when instruments of all kinds are better understood, has captivated the musical world in, perhaps, a still higher degree; but whether the duration of his favour will be equal to that of Corelli, who reigned supreme in all concerts, and excited undiminished rapture full half a century, must be left to the determination of time, and the encreased rage of depraved appetites for novelty.

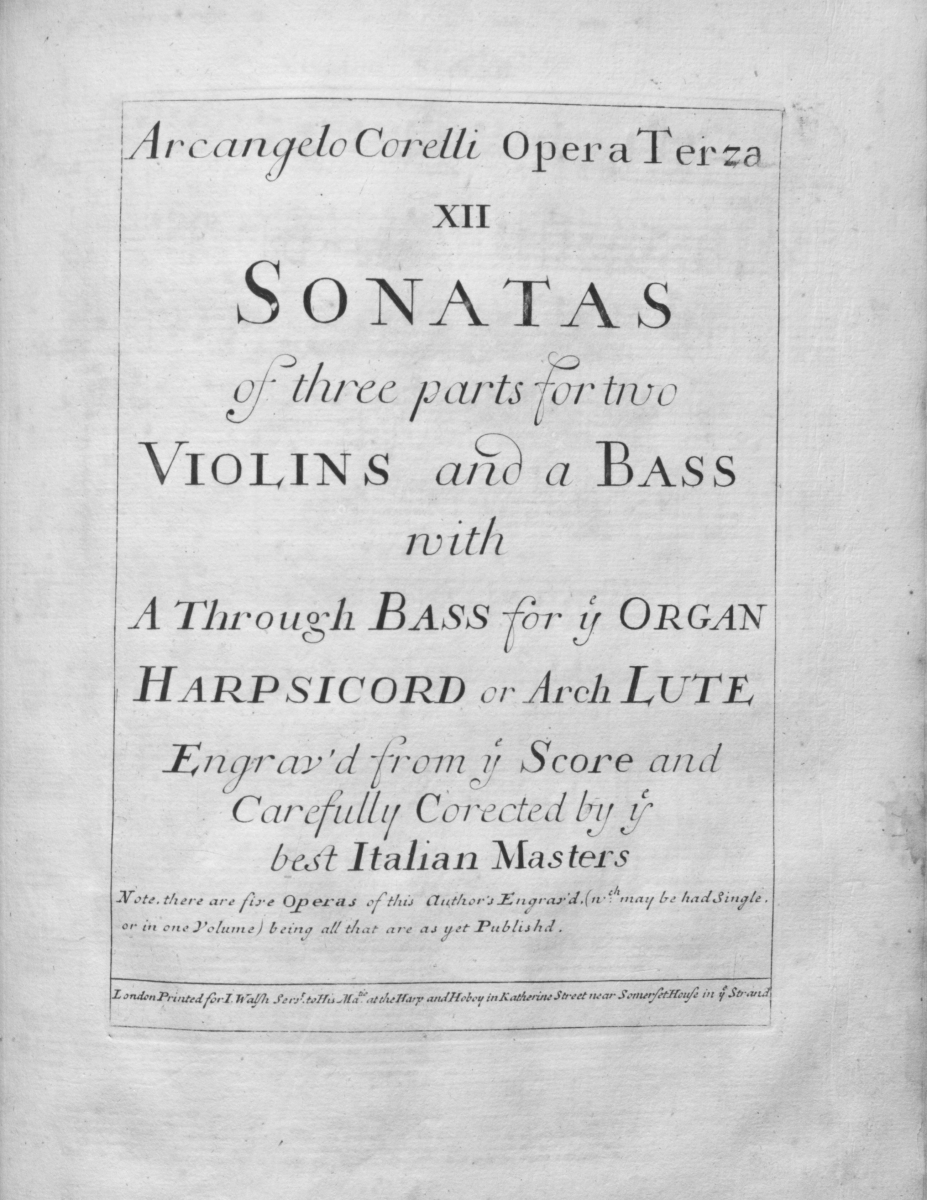

The popularity of the Corellian style may be judged by the phenomenal number of reprints enjoyed by the six published works between the time of their appearance and the end of the eighteenth century. The solo sonatas of Op. 5 were, predictably, the most frequently reissued, with at least forty-two editions by 1800, but the trio sonatas did not lag far behind. Op. 3, for example, first appeared in Rome in 1689, but was also put to the press within the same year in Bologna and Modena, in 1691 at Venice and Antwerp, again in 1694 in Venice, and the following year once more in Bologna and Rome. Over the next several decades, four more Italian reprints appeared, but the real surge in the dissemination of these sonatas occurred in northern musical centers. The Amsterdam publisher Estienne Roger issued his first Op. 3 print in 1706, and six more editions appeared for sale in the Netherlands within the next twenty years. New copies of the Op. 3 sonatas appeared in Paris in or about 1718, 1719, 1740, and 1763. England was even more Corelli-crazed, with Op. 3 offered in London in ca. 1720, 1728, ca. 1735 (by five different publishers!), ca. 1740, ca. 1754, ca. 1765, and ca. 1790. Similar figures might be cited for the other trio sonata collections; nor were these the only Corellian works to enjoy such general approbation. Geminiani arranged six trio sonatas from Corelli’s Opp. 1 and 3 and all twelve of the Op. 5 solo sonatas as concerti grossi in the 1720s and ’30s. Unabashed imitators of Corelli’s style were abundant, perhaps the most famous being his pupil John Ravenscroft, who published a set of trios at Rome in 1695 so like their models that they were reprinted by Le Cene as “Corelli’s Op. 7” some forty years later.

While such emulation presents telling witness to the attraction of the Corellian style, it is in the pages of Hawkins’s History that we find perhaps the most moving appraisal of Corelli’s importance:

It is said [by Samuel Johnson in the preface to his edition of Shakespeare] there is in every nation a style, both in speaking and in writing, which never becomes obsolete; a certain mode of phraseology, so consonant and congenial to the analogy and principles of its respective language, as to remain settled and unaltered. This, but with much greater latitude, may be said of music; and accordingly it may be observed of the compositions of Corelli, not only that they are equally intelligible to the learned and unlearned, but that the impressions made by them have been found to be as durable as general. His music is the language of nature; and for a series of years all that heard it became sensible of its effects; of this there cannot be a stronger proof than that, amidst all the innovations which the love of change had introduced, it continued to be performed, and was heard with delight in churches, in theatres, at public solemnities and festivals in all the cities of Europe for near forty years. Men remembered, and would refer to passages in it as to a classic author; and even at this day the masters of the science, of whom it must be observed, that though their studies are regulated by the taste of the public, yet have they a taste of their own, do not hesitate to pronounce of the compositions of Corelli, that, of fine harmony and elegant modulation, they are the most perfect exemplars.

THE OP. 3 TRIO SONATAS

The entries for sonata in various editions of Sebastian de Brossard’s Dictionaire de musique (France’s first such dictionary, initially published in 1701) serve as useful reminders of how Corelli’s contemporaries viewed the genre:

Sonatas are ordinarily extended pieces, varied by all sorts of emotions and styles, according to the fancy of the composer. There are sonatas of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 parts, but most usually they are for violin alone or for two violins with a basso continuo for the harpsichord, and often a more florid bass part for the viola da gamba or bassoon, etc. Thus there is an infinite variety of styles possible, but the Italians ordinarily reduce them to two types. The first comprises the Sonatas da chiesa—that is, proper for the church—which differs from the second, comprising the Sonatas da camera—that is, proper for chamber use—in that the movements of the da chiesa type are Adagios or Largos, etc., mixed with fugues that provide the Allegros; while the movements of the da camera type consist, after the Adagio, of dance pieces such as an Allemande, a Courante, a Sarabande, and a Gigue. . . . For models see the works of Corelli.

Corelli published his twelve trio sonatas, Op. 2, in 1685 as Sonate da camera a tre. While the Op. 1, 3, and 4 trio sonatas (first issued in 1681, 1689, and 1694, respectively) bear no indication beyond Sonate a tre, it is easy, following Brossard’s definition, to pair Opp. 1 and 3 under the da chiesa rubric, and group Op. 4 with Op. 2 as examples of the da camera form. As sonatas of the late eighteenth century very often fail to conform to the textbook standards established in the first decades of the nineteenth century for the Classical period sonata-allegro, so Corelli’s sonatas soften the rigid contours of Brossard’s depictions, though their general outlines are clear enough. Roger North’s early eighteenth-century writings include a colorful guide to a church sonata that may be applied, with only slight deviations, to the majority of the Op. 3 works:

The entrance is usually with all the fullness of harmony figurated and adorned that the master of that time could contrive, and this is termed Grave. This Grave most aptly represents seriousness and thought. The movement is as of one so disposed, and if he were to speak, his utterance would be according, and his manner rational and arguing. The upper parts only fullfill the harmony, without any singularity in the movement; but all joyne in a comon tendency to provoke in the hearers a series of thinking according as the air invites, whether Magnifick or Querolous, which the sharp or flat key determines. When there hath bin enough of this, which if it be good will not be very soon, variety enters, and the parts fall to action, and move quick; and the entrance of this denouement is with a fugue. This hath a cast of business or debate, of which the melodious point is made the subject; and accordingly it is wrought over and under till, like waves upon water, it is spent and vanisheth, leaving the musick to proceed smoothly, and as if it were satisfyed and contented. After this comes properly in the Adagio, which is a laying all affaires aside, and lolling in a sweet repose: which state the musick represents by a most tranquil but full harmony, and dying gradually, as one that falls asleep. After this is over Action is resumed, for the most part concluding with a Gigue which is like men (half foxed) dancing for joy, and so good night.

Hawkins, surveying the forty-eight Corelli trios, found those of Op. 3 the most elaborate, as abounding in fugues. The first, the fourth, the sixth, and the ninth Sonatas of this opera are the most distinguished; the latter has drawn tears from many an eye; but the whole is so excellent, that, exclusive of mere fancy, there is scarcely any motive for preference. Johann Sebastian Bach’s use of the fugal subject of the second movement of Op. 3, No. 4, in his organ fugue BWV 579, is further testimony to the pithy excellence of Corelli’s contrapuntal material.

PERFORMANCE NOTE

The original title page for the Op. 3 sonatas reads, in part: Sonate a tre, doi Violini, e Violone, o Arcileuto / con basso per l’Organo (“Trio sonatas, for two violins and violone or archlute, with organ continuo”). This instrumentation is typical of late seventeenth-century Italian works in offering the archlute (theorbo) as a possible substitute, not for the organ, which shares with the lute the capacity for playing chords to realize the figured bass, but for the violone (understood in this usage to be a large cello-like instrument playing in the 8′ register). A careful comparison of a large number of baroque title pages and bass parts suggests, however, that o (“or”) and e (“and”) were often used almost synonymously in such contexts. Title pages proclaiming a choice between two bass instruments were not infrequently accompanied by bass parts labelled with the names of both instruments. Such doubling of the bass line became even more frequent in the eighteenth century (though it was of course possible to give a leaner reading with only one bass instrument, or with harpsichord). Since Corelli’s sonatas had such longevity, and since iconographic depictions of several bass-line players reading from a single piece of music are numerous, we decided to employ a number of different continuo combinations (theorbo, violone, and organ; violone and organ; theorbo and organ) to take full advantage of the broad palette of timbres the presence of three bass instruments affords.

***

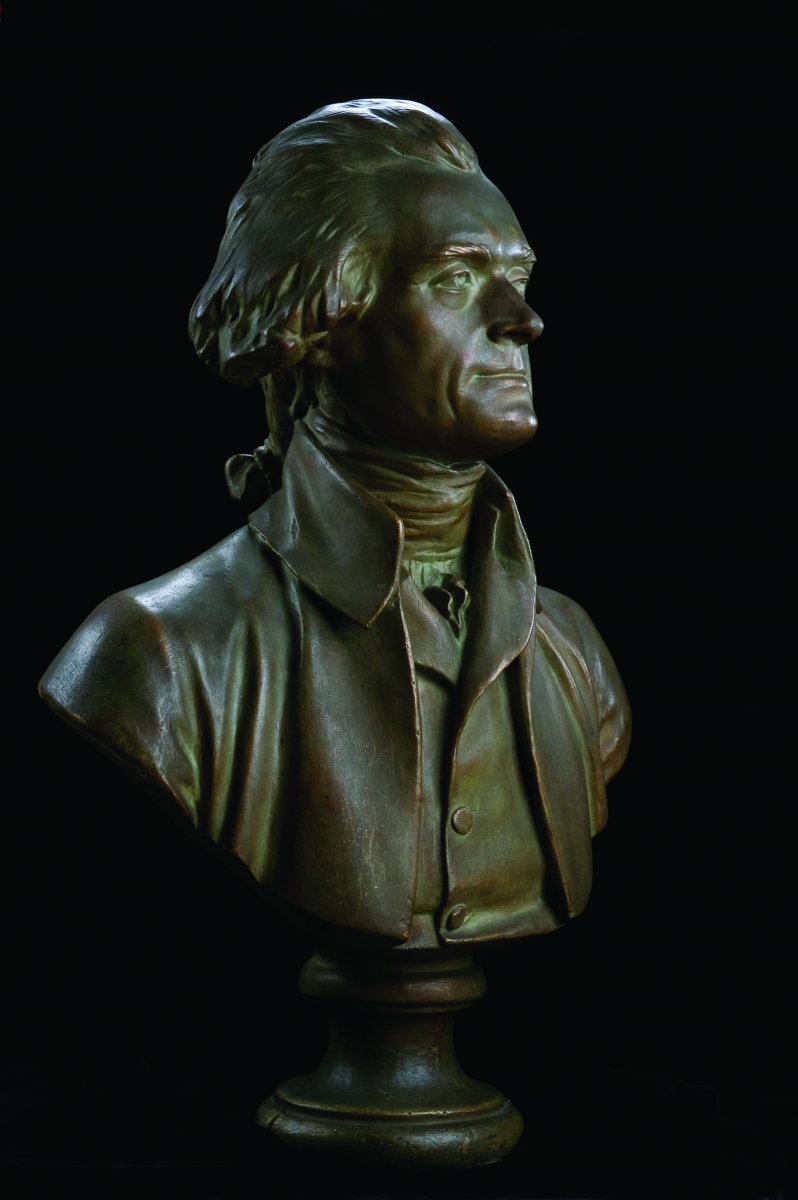

Music furnishes a delightful recreation for the hours of respite

from the cares of the day, and lasts us throughout life.

So wrote the seventy-four-year-old Thomas Jefferson in 1818, eight years before his death. Though nothing is known about his first encounters with the Euterpean muse, Dumas Malone’s magisterial biography, Jefferson and His Time (6 volumes, published between 1948 and 1981) relates that by the time he enrolled as a boarder at the Reverend William Douglas’s Latin School at the age of nine in 1752, he could play the violin and read music. Six years later, a dancing master was engaged for six months to train Jefferson and his four sisters in one of the important social graces of the period. Violin playing was Jefferson’s favorite indoor amusement during the three years he spent at the Reverend James Maury’s boarding academy before entering the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1760. Jefferson later recalled that the previous Christmas season, he had spent several weeks dancing with the company assembled at his host’s house and playing violin duets with future Virginia governor Patrick Henry. After completing his college studies in 1762, Jefferson apprenticed in the law office of George Wythe, who introduced him to the Royal Governor of Virginia, Francis Fauquir, who was, according to Jefferson, “an admirable violinist” who invited Jefferson to join his weekly chamber music parties. According to a “Memorandum” penned in 1826 by his grandson-in-law, Nicholas Philip Trist, Jefferson claimed to have practiced the violin for three hours a day “for a dozen years” during the 1760s and 1770s. After marrying Martha Wayles Skelton on New Year’s Day, 1772, Jefferson took his new bride to his Palladian villa at Monticello (then, as it would always remain during Mrs. Jefferson’s lifetime, under construction), and shortly thereafter invited the Italian immigrant music master Francis Alberti to move from Williamsburg to Charlottesville for the express purpose of giving violin and harpsichord lessons to the young couple.

Helen Cripe’s Thomas Jefferson and Music traces Jefferson’s involvement with his “delightful recreation” through examination of the instruments he owned, the concerts he attended (particularly those he heard in Paris, 1784–89, while he was Minister to France), his catalogue of his personal music collection, and the surviving Monticello Music Collection—now housed in the University of Virginia Library at Charlottesville—containing numerous hard-bound volumes, string-bound collections, and loose sheets of music belonging to various members of the Jefferson family, principally his wife, daughters, and granddaughters. The extent to which Jefferson sought to integrate music into his life at Monticello is clear in a letter of 1778 he wrote to Giovanni Fabbroni, a friend of the Italian Philip Mazzei, who, during his first sojourn in Virginia (1773–79) established with Jefferson what would become the first commercial vineyard in the Commonwealth of Virginia. After a rather lengthy discussion of the course of the Revolutionary War, Jefferson turned to what he called “the favorite passion of my soul:”

If there is a gratification which I envy any people in this world it is to your country its music. This is the favorite passion of my soul, and fortune has cast my lot in a country where it is in a state of deplorable barbarism. . . . The bounds of an American fortune will not admit the indulgence of a domestic band of musicians. Yet I have thought that a passion for music might be reconciled with that economy which we are obliged to observe. I retain for instance among my domestic servants a gardener (Ortolano), weaver (Tessitore di lino e lano), a cabinet maker (Stipettaio) and a stonecutter (scalpellino lavorante in piano) to which I would add a Vigneron.

In a country where, like yours, music is cultivated and practiced by every class of men, I suppose there might be found persons of those trades who could perform on the French horn, clarinet or hautboy [oboe] and bassoon, so that one might have a band of two French horns, two clarinets and hautboys and a bassoon, without enlarging their domestic expenses. A certainty of employment for a half dozen years, and at the end of that time to find them if they chose a conveyance to their own country might induce them to come here on reasonable wages. Without meaning to give you trouble, perhaps it might be practicable for you in your ordinary intercourse with your people to find out such men disposed to come to America. Sobriety and good nature would be desirable parts of their characters. If you think such a plan practicable, and will be so kind as to inform me what will be necessary to be done on my part, I will take care that it shall be done.

Though Jefferson’s plan for a musical domestic staff never achieved fruition, it would have provided for a small Harmonie, or wind band, which could function either on its own, or when joined by amateur string players like Jefferson, as the basis for a small orchestra. (Gentlemen often learned stringed instruments rather than risk having to “puff out the face in a vulgar fashion” by playing winds.) Later, in 1805, President Jefferson launched a successful campaign to bolster the abilities of the Marine Band (which had been established in 1798, and exists to this day as the oldest continuing professional music organization in the United States) by instructing one Captain John Hall, who was serving in the Mediterranean during the Barbary Coast War (an action memorialized in a line of the Marines’ Hymn—“to the shores of Tripoli”), to enlist some Italian musicians for service in America. A group of over a dozen Sicilian players, led by Gaetano Carusi, took up their posts in September of that year in what Carusi described as “a desert; in fact a place containing some two or three taverns, with a few scattered cottages or log huts, called the City of Washington, the metropolis of the United States of America.”

Jefferson’s sale of his own carefully compiled library to the United States Congress in 1815 certainly had a salubrious effect on the cultural foundations of that young metropolis. A manuscript catalogue of the library (bearing the date “6 March 1783” and known therefore as “the 1783 catalogue,” even though it continued to be revised by Jefferson until the time of the sale) contains among its many chapters three pertaining to music: chapter 35, “Music Theory;” chapter 36, “Vocal;” and chapter 37, “Instrumental;” with the last being the most extensive. Not surprisingly, compositions involving violin or harpsichord, gathered by Jefferson during his travels, comprise the majority of the entries. The composers represented in addition to Corelli include other English favorites such as Carl Friedrich Abel (1723–87), Johann Christian [“the London”] Bach (1735–82), Georg Friderick Handel (1685–1759), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), the much-traveled Francesco Geminiani (1687–1762), Felice de Giardini (1716–96), Gaetano Pugnani (1731–98), who also worked in Paris, Giovanni Battista Lampugnani (1708–88), Quirino Gasparini (1721–78), Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–36), and Samuel Arnold (1740–1802). Jefferson’s library also contained works by a number of Paris-based (or Paris-published) composers such as Jean Baptiste Lully (1632–87), Carlo Antonio Campioni (1720–88), Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805), Wenceslaus Wodizka (ca. 1717–74), and Carlo Tessarini (ca. 1690–1766) and Carl Stamitz (1745–1801), who were also active in London.

As Shandor Salgo points out, in his Thomas Jefferson: Musician and Violinist, Jefferson kept three commonplace books while he was a student. Two pertained to aspects of law, and a third, known as his Literary Commonplace Book, contained quotations from his omnivorous readings in English, French, Latin, and Greek. The practice of keeping commonplace books was widespread for several centuries, and was intended to impress on the compiler’s memory the sentiment of the entries contained therein, and to act as a ready reference in case verbatim recall was required. The quotations so gathered served their transcriber as a kind of moral compass. Jefferson’s inclusion of the following lines from Act V, scene 1 (lines 81 ff) of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (slightly altered, whether by Jefferson himself or from some intermediate source) is thus of no small utility to those who would seek to understand the importance of music to the future President:

What so hard, so stubborn, or so fierce,

But Music for the Time will change its Nature?

The Man who has not Music in his soul,

Or is not touched with Concord of sweet Sounds,

Is fit for Treasons, Stratagems and Spoils;

The motions of his Mind are dull as Night

And his Affections dark as Erebus:

Let no such Man be trusted.

(from the liner notes to the recording by Kenneth Slowik, ©2013)